operating systems showdown

Modern open source operating systems vs modern software development practices

The reason to write this blog post was a presentation I watched some time ago, and commented on it on Twitter:

One of the slides from the presentation. How can you develop an operating system and follow *that* kind of process?! :sadpanda: pic.twitter.com/3XuHMXc0My

— Marcin Cylke (@zygm0nt) January 5, 2020

So to be specific - the whole presentation was rather negative towards security model used along OpenBSD development. The presentation itself took a lot of time to go over recent security issues, false claims, etc.

What strikes me in it was how the development process for that particular operating system actually looks like. Working with software for quite some time now I have a pretty decent idea of how the development process of my half baked, security-assed code actually look like.

All that got me wondered - how OS developers actually deal with their daily load of issues? How do they fix bugs, monitor simple security issues, regressions, etc? And also what’s their tooling around that? It’s easy to say - just use git, or JIRA, or any other “normal” dev tool. But since you’re developing an actual OS things are’ perhaps’ not that obvious anymore. The code bases tend to be huge. With the multitude of contributions, mighty loads of bugreports.

The comment was about OpenBSD, but then I started wondering - how does this process actually look like for other major (or not necessarily) operating systems?

So I’ve decided to take some time and look into that space. I wanted to look into a few operating systems I tend to use, used to use, or just keep an eye for. Some of those are the key players in the OS space, some are just hobby projects. For all of them I just wanted to get a picture of how the development process looks.

Please keep in mind that this should be regarded mostly as a beginners guide, I have no significant experience in contributing to any of those code bases, so I was also looking into how approachable each of those communities is for newcomers. Also there may be a lot of obvious omissions for experienced contributions, but if it’s not mentioned in this post than I had a hard time finding relevant information - so anything that is a “secret lore” circulating among experienced contributors is not enough for me, a newbie.

With that disclaimer out of the way, I’d really welcome comments about my findings, so if you have any fell free to reach out to me and help with clarifying things here.

The process as I see it

So what actually constitutes the development process of a software project? Well for me this can be summed up into how the project handles the following key areas:

- how should I approach the codebase when I want to start contributing to the code

- what if I find a bug? how that looks like?

- what happens when I submit the bugreport?

- how the code is tested for regressions, or tested in general?

A good deal of this questions can actually be answered by discovering how each of those systems approach:

- VCS

- Testing

- code-review process

Rationale for including each of the systems in this comparison

- Linux - well, I just use it the most theses days. Which is fine, since the kernel is such a great code with a lot of innovative things happening. But since with just the kernel you can’t actually do that much, you always choose a specific distro that serves all your user needs. This comparison thou focuses solely on the kernel development process. I don’t want to delve into the fragmented space of Linux distros and they’re own ideas. I feel it would just dilute the overall impression of the efforts around Linux as a platform.

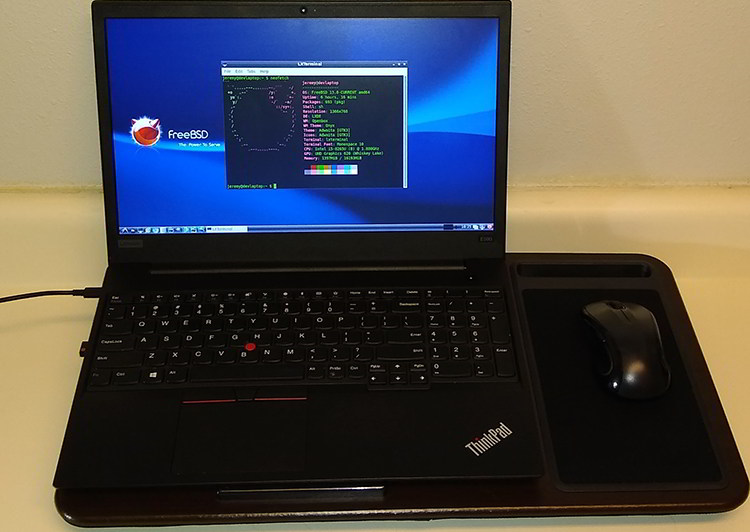

- FreeBSD - a system I’ve been using for a really long time. It has all the great ideas of the BSD family, is extremely coherent in vision, as are all BSD systems since they’re not just a kernel but a whole package. You get kernel and userland with all the tools and basic integrations, which in my opinion is great. Choosing a specific BSD flavor actually means something, and not just a different UI experience as in the case of Linux.

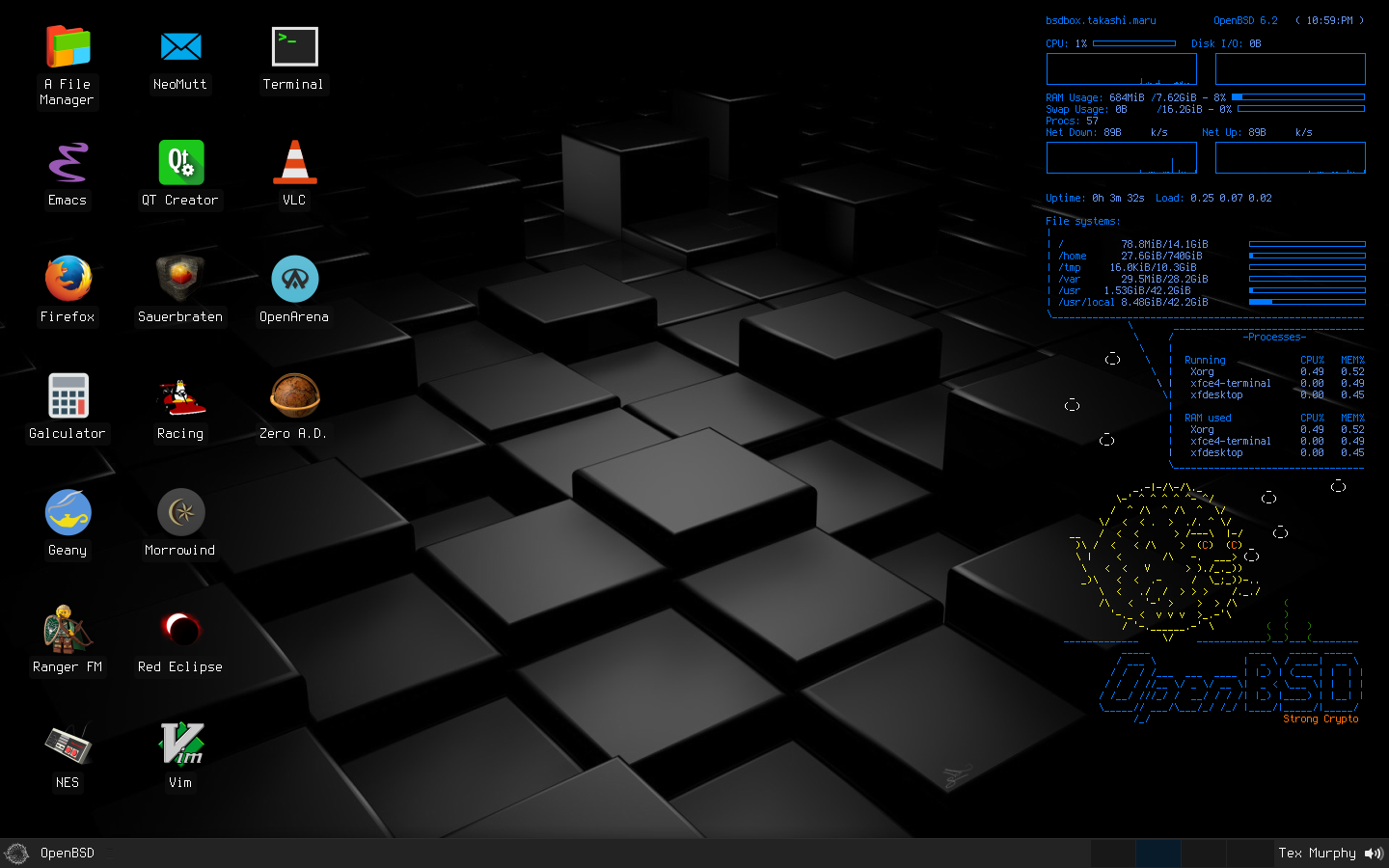

- OpenBSD - the reason this blogpost came to being, but I wouldn’t watch the presentation in the first place if not for me previous interest in this flavor of BSD. It was actually the first of the BSDs I’d started using. Liked it for it’s compactness, great documentation, ease of installation,

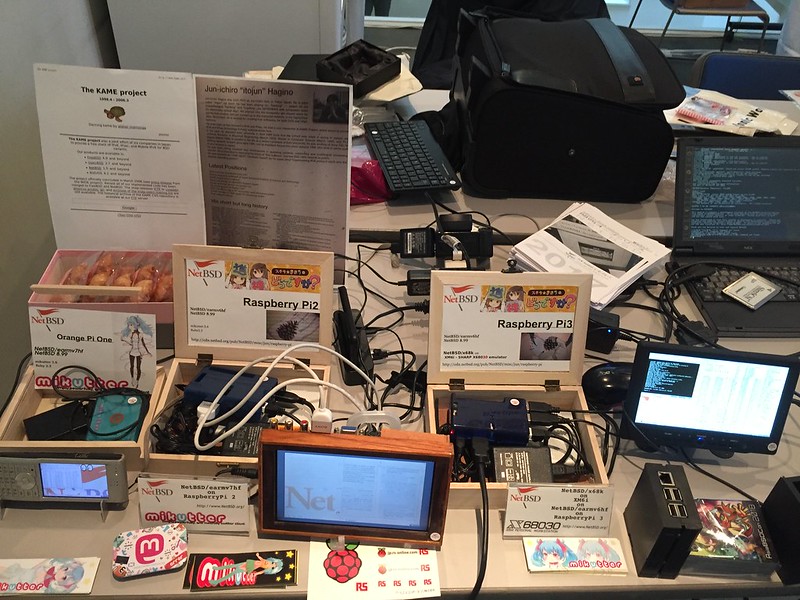

- NetBSD - I’ve actually haven’t installed it, not even once. But this is such a great example of a system that tries to keep all those obsolete machines (which I adore) alive, I just couldn’t omit it from this comparison. Also what’s even more important, OpenBSD at some point forked from NetBSD due to difference in opinions between core developers. So both systems have common roots, let’s see how they actually compare,

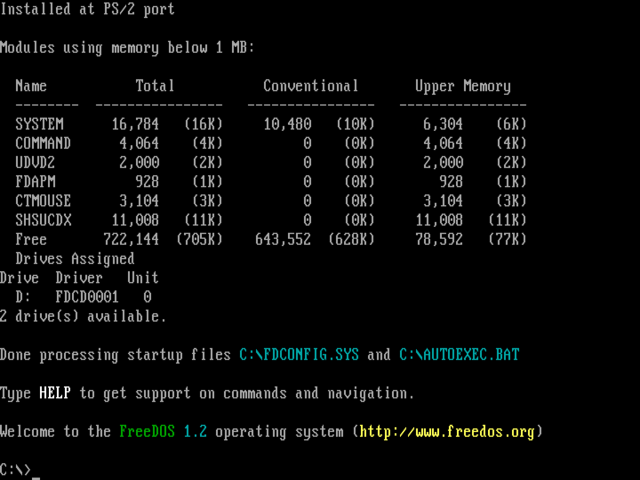

- FreeDOS - a free reimplementation of DOS - seems pretty complete and finished at this point, but since it’s still used in multiple places the community around it is quite vibrant,

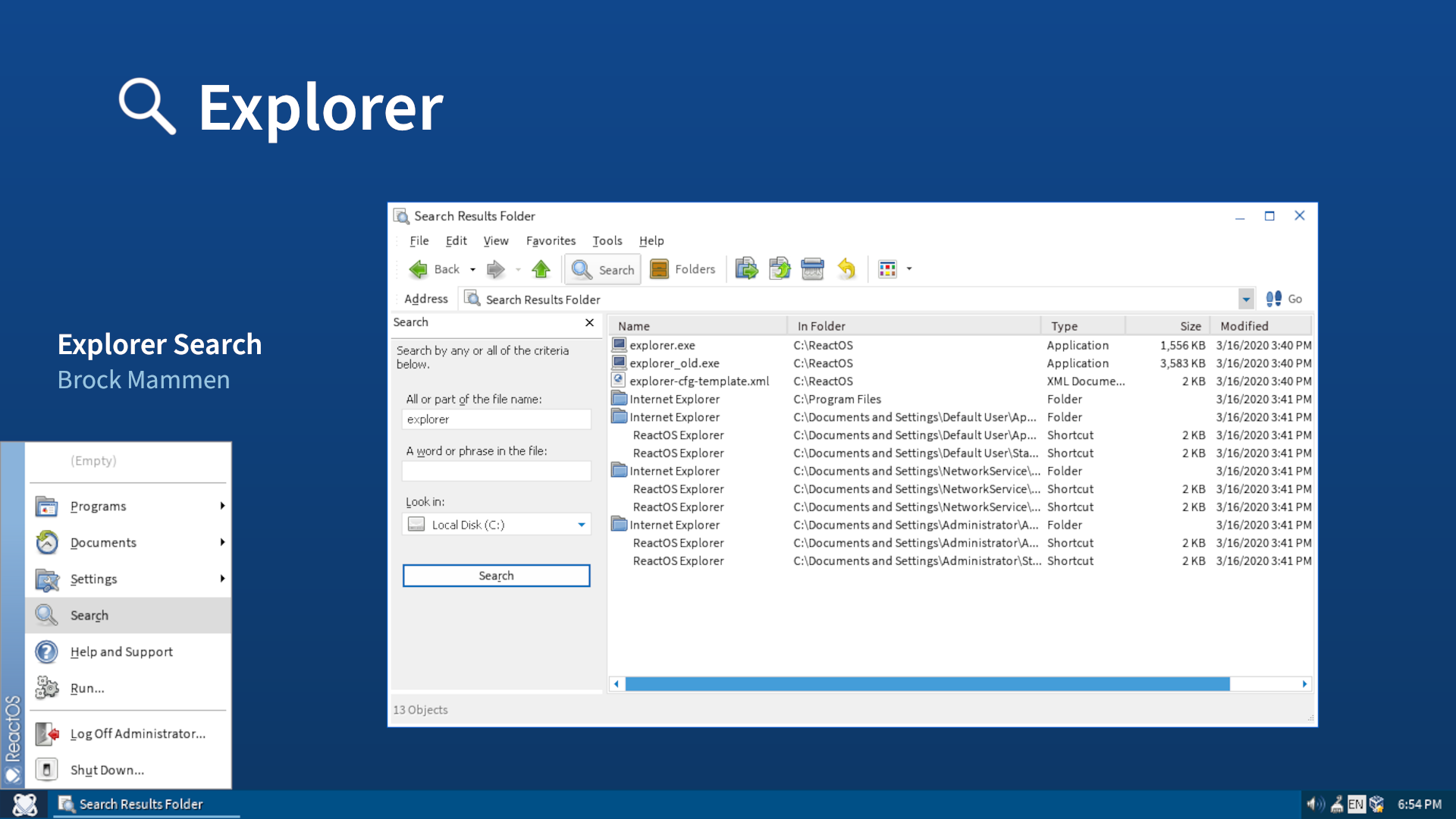

- ReactOS - another reimplementation - but this time of the Windows 95/2000 line of systems. It has this ambitious goal to be able to run Windows programs without problems. All this being accomplished with a lot of reverse engineering and of the original implementations. Last time I’ve check I still couldn’t run some programs I needed, but the effort is impressive enough for me to keep an eye on it from time to time.

Linux

This is somewhat different, as due to its nature refers solely to the kernel. Other OSes in this comparison store kernel+base system in their repos.

- Docs

- Good first-timer commiter guide https://kernelnewbies.org/UpstreamMerge

- Comprehensive guide to dealing with kernel development: https://www.kernel.org/doc/html/latest/

- With tools like https://git.kernel.org/pub/scm/linux/kernel/git/torvalds/linux.git it’s easy to trace what changed with every commit

- Bug reporting

- VCS

- Git: https://github.com/torvalds/linux

- Another view on the kernel sources: https://git.kernel.org/pub/scm/linux/kernel/git/torvalds/linux.git

- Awesome kernel repositories: https://www.kernel.org/

- Multiple categories of releases: https://www.kernel.org/category/releases.html

- Testing

- There’s some initiative for Continuous testing of kernel branches: https://kernelci.org/ - “It is our mission to detect, bisect, report and fix regressions on upstream Kernel trees before they even reach «mainline».”

- https://embeddedbits.org/how-is-the-linux-kernel-tested/

- Reviews

- Why Patches are still submitted via email: https://lwn.net/Articles/702177/

- Generally no performant solution to keep track of changes Linux Kernel sees,

- “ the quality of email clients is not uniformly good. Some systems, like Outlook, will uniformly corrupt patches; as a result, companies doing kernel development tend to keep a Linux machine that they can use to send patches in a corner somewhere. Gmail is painful for sending patches, but it works very well as an IMAP server. Project managers, he noted, tend not to like email. He seemed to think of that as an advantage, or, at worst, an irrelevance, since the kernel’s workflow doesn’t really have any project-manager involvement anyway.”

- There’s a trace of review process in each commit: https://git.kernel.org/pub/scm/linux/kernel/git/torvalds/linux.git/commit/?id=dcf23ac3e846ca0cf626c155a0e3fcbbcf4fae8a

- < Screenshot of the signature metadata>

- All commits are signed by their respective authors

- Description of the patch submit process : https://www.kernel.org/doc/html/v4.17/process/submitting-patches.html

FreeBSD

- Docs

- There’s a commiter’s Handbook: https://www.freebsd.org/doc/en_US.ISO8859-1/articles/committers-guide/article.html

- Bug reporting

- VCS

- Subversion as primary VCS: https://www.freebsd.org/doc/en_US.ISO8859-1/articles/committers-guide/article.html#subversion-primer

- in the process of moving to git:

- Multiple branches

- Separate repos for ports, docs, base system

- CURRENT as the development branch, with release cut offs along the way

- There is a read-only mirror of the code repo on GitHub: https://github.com/freebsd/freebsd

- At some point in time I’ve heard that FreeBSD uses Perforce repo, but found only mentions that it’s used for experimental stuff or work for Google Summer of Code:

- An article from 2013 about the use of perforce: https://docs.freebsd.org/doc/10.0-RELEASE/usr/local/share/doc/freebsd/en/articles/p4-primer/article.html

- https://wiki.freebsd.org/Perforce

- Testing

- Each change has build status, and automatic test status: https://reviews.freebsd.org/D24120

- Even linting

- Seems that CI server being used is https://cirrus-ci.com/ - but the integration is unclear. I was unable to access CirrusCI from Phabricator

- Testing with Coverity: https://wiki.freebsd.org/CoverityPrevent

- Review

- Phabricator: https://wiki.freebsd.org/Phabricator, https://reviews.freebsd.org/

- Documented here: https://www.freebsd.org/doc/en_US.ISO8859-1/articles/committers-guide/pre-commit-review.html

- So according to that - for pre-commit reviews there are multiple ways: email, in Bugzilla, in Phabricator, or by another mechanism.

OpenBSD

- Docs

- the docs are very well written. They’re consistent and easy to follow. The official docs can be found here

- Bug reporting

- Docs on creating bug report: https://www.openbsd.org/report.html

- This quote is taken from the official docs - If possible, use the sendbug(1) command to help generate your bug report. It will automatically include some useful information about your hardware that helps diagnose many issues. This tool requires that your system can properly send email. If you cannot use sendbug on a functional OpenBSD machine, please send your bug report to bugs@openbsd.org.

- and here is the description of this tool for bugreports https://man.openbsd.org/sendbug

- Bugs’ archive available here: https://marc.info/?l=openbsd-bugs

- No intention to actually have a bugtracker:

- http://openbsd-archive.7691.n7.nabble.com/bug-tracking-system-for-OpenBSD-td321009.html - or to be more precise there’s none willing to commit time to this project. Also here’s a nice quote from Ted Unangst about the potential approach:

not underestimate the effort involved.

so this has come up before, and the answer remains the same. anyone can setup a bug tracker, and feed bugs into it. close the ones that get fixed, categorize the rest, etc.. do that for a few months and see how it goes.

i’m not really interested in looking at an empty bug database. nor one that’s filled with crap. so yeah, there’s a bootstrapping problem.

you don’t have to announce your bug database the first day you set it up. in fact, it’s better not to. but in a few months time, when somebody inevitably asks misc how do i contribute, where’s the todo list, you’ll have this handy list of unresolved bugs to point them at.

like a lot of projects that seem really easy, you’d think somebody would just do it if it were that simple. but the idea that nobody wants to chance investing time in a deadend project suggests they kind of know the time investment isn’t just a saturday afternoon.

- Here’s more on no intention to have a bugtracker https://www.mail-archive.com/misc@openbsd.org/msg160396.html with the quote being:

If you look at a successful bug tracker, you will not be able to see most of this work without grovelling through dead tickets because the already-fixed issues and veiled support requests will no longer be visible.

-

With hostile attitude like this one: https://www.mail-archive.com/misc@openbsd.org/msg160410.html

-

VCS

- CVS

- Read only mirror: https://github.com/openbsd “Public git conversion mirror of OpenBSD’s official CVS src repository. Pull requests not accepted - send diffs to the tech@ mailing list.”

- There are certain parts of OpenBSD or those that were developed as part of the project, which are available outside CVS, and accept patches via GitHub:

-

Testing

- Haven’t found any build farm, continuous integration

- Possible to run distributed port builder https://man.openbsd.org/dpb.1 - but no effort to do this officially

-

Review process

- no formalized process in place, except for reviews on mailing lists

-

Hackathons

- Themed hack events a few times a year

- https://www.openbsd.org/hackathons.html

- Good summaries of those to be found here: https://undeadly.org/cgi?action=front

-

Update process

- Patches for the system https://www.openbsd.org/errata66.html

- syspatch(8) - apply security and reliability updates.

- sysupgrade(8) - upgrade to the next OpenBSD release or a newer snapshot.

- https://flak.tedunangst.com/post/rethinking-openbsd-security

NetBSD

- Docs

- Useful commiter docs here: https://www.netbsd.org/developers/commit-guidelines.html

- VCS

- Still uses CVS https://www.netbsd.org/developers/restricted.html#rsync

- Testing

- there’s a set of automated tests, and also documentation on how to write more of that: https://wiki.netbsd.org/tutorials/atf/

- there’s a build farm with somewhat automated testing process https://gdb-buildbot.osci.io/#/builders/10

- also there’s a daily build log for a few major branches https://releng.netbsd.org/cgi-bin/builds.cgi

- Review

- Tickets and release engineering

- the whole release engineering process is described here https://releng.netbsd.org/

- bug reporting is done by email - posting bug messages into a specific mailing list

- there are bug status logs for each release: https://releng.netbsd.org/index-9.html

FreeDOS

- Docs

- main wiki for the project can be found here http://wiki.freedos.org/wiki/index.php/Main_Page

- they have this awesome notion of intentional releases http://wiki.freedos.org/wiki/index.php/Releases/1.3 which is very nice because it brings focus to the process. Although I’ve found just two of those pages :)

- a complete docs can be found on FTP servers, they’re compressed and best viewed after downloading and unzipping http://www.ibiblio.org/pub/micro/pc-stuff/freedos/files/dos/help/1.08/

- VCS

- Github based https://github.com/FDOS/kernel

- Bugs

- Sourceforge bugtracker: https://sourceforge.net/p/freedos/bugs/

- this is quite sad. For me sourceforge is quite a legacy platform, dated and slow. Seems everything alive have already moved elsewhere, so I hope this does not mean some stagnation for FreeDOS.

- Testing

- Travis-CI checks for PRs: https://github.com/FDOS/kernel/pull/16/checks

ReactOS

- Docs

- Decent docs on how to start contributing: https://reactos.org/wiki/Development_Introduction

- VCS

- Git: https://reactos.org/wiki/Building_ReactOS

- Changes maintained via Git pull requests

- Testing

- There’s automatic regression testing: https://reactos.org/testman/

- Don’t see any automatic testing on per-Pull Request level

- Review

- Tasks kept in Jira https://jira.reactos.org/browse/CORE-13950

- Review in Git

Comparison table

| OS name | VCS | Code review | Bug reporting | Contributors guide |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linux | Git | |||

| Freebsd | SVN / migrating to Git | Phabricator | Bugzilla | commiters guide |

| Openbsd | CVS / Github based Git readonly mirror | CVS - core system, review via email, / Github pull-requests for GH-based projects | No intention to have a bugtracker | |

| Netbsd | CVS | commiters guide | ||

| FreeDOS | Git | Github-based | sourceforge tracker | |

| ReactOS | Git | reviews in git | JIRA | how to start contributing |

Conclusion

The mentioned operating systems differ greatly in terms of modern tools adoption. The whole endeavor started as a way to compare how grounded in reality accusations towards OpenBSD really are. And from what I’ve found, also judging by the seemingly strong security concerns of Openbsd’s maintainers, and relative popularity of the OS itself, I must say that it now seems nothing more than a hobby OS, or a niche one, with usage in specific places like isolated network infrastructure. Not the one that should really be accessible from the outside world in any way. The effort around the OS has brought us a good deal of really useful and secure solutions, but as a whole its development process seems dubious.

As for the other Operating Systems - the clear contenders here are Linux and FreeBSD.The former as an unprecedented leader in terms of focus and the amount of contributions from various vendors and independent developers, and the latter because of the exquisite quality of the source code and value it brings to the table despite being foreshadowed by The Penguin.